Chapter Precap

The Indian Urban Paradox & Hidden Realities

| Structural Bottlenecks: Land, Mobility & Finance

|

Redefining Informality & Resource Management

| The Social Contract & Design Philosophy

|

Introduction

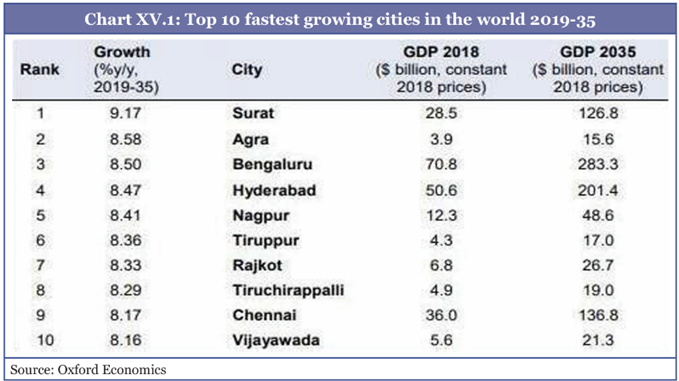

- The Economic Logic of Agglomeration: The cities exist to facilitate agglomeration economies.

- These agglomerations, over time, assume the role of a 'city' when they cross three thresholds simultaneously:

- Demographic scale and density sufficient for sustenance of multiple non-agrarian livelihoods

- This density is a driver of wealth.

- Economic diversification in terms of presence of multiple avenues of non-agrarian livelihoods, and

- Institutional recognition through presence of an urban local body, statutory boundary, or formal planning authority.

- Demographic scale and density sufficient for sustenance of multiple non-agrarian livelihoods

- Research indicates that in developing economies like India, doubling a city's size typically boosts productivity by 12 per cent

- These agglomerations, over time, assume the role of a 'city' when they cross three thresholds simultaneously:

- The Indian Urban Paradox: The Survey argues that population scale has not resulted in proportionate global economic influence or liveability because infrastructure investment has lagged behind growth. As a result, the potential benefits of density have been diluted by congestion, environmental stress, and informalisation. Identifying the binding constraints of this paradox:

- Supply-side Constraints: There are persistent deficits in the hard infrastructure of cities, specifically land, housing, and mobility.

- Institutional Fragmentation: A major hurdle is the governance architecture, where authority is splintered across various bodies and cities lack the fiscal autonomy to plan and finance their own development.

- Intangible Foundations: The quality of urban life depends heavily on trust and collective behaviour regarding shared spaces.

- The Necessary Strategic Shift: It argues that the cities must be treated as economic assets that require deliberate strategic planning and investment to transform urbanisation into a source of well-being and opportunity.

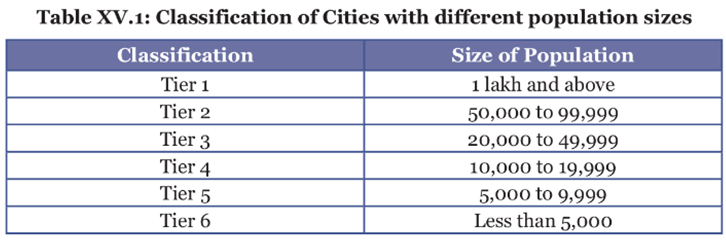

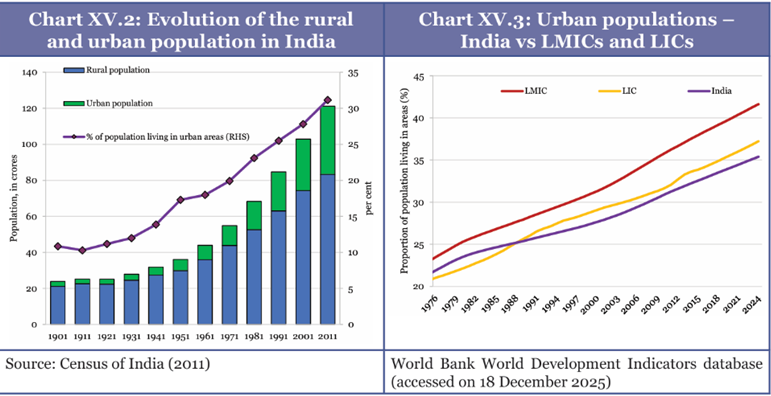

Trends in India's Urbanisation

- The Official Slowdown vs. Hidden Urbanisation According to the census definition, India's urbanisation has been slowing but the chapter argues that India is hiddenly urban. When observed through alternative metrics like mobility, built-up area, and satellite data, the picture changes drastically:

- Spatial Expansion: The Night-Time Lights (NTL) data to visualise where people actually live and work, revealing that Indian cities are expanding horizontally rather than vertically.

- It is said that census hypothesises could be due to the "ruralisation of industry" whereby rural areas account for a significant chunk of manufacturing output.

- Satellite Evidence: Using the Degree of Urbanisation (DEGURBA) methodology and data from the European Commission, international bodies estimated India to be 63 per cent urban as of 2015 (nearly double the rate reported in the 2011 Census).

- Core-Periphery Ratio: In 16 major cities, the periphery grew faster than the urban core between 2000 and 2020.

- This confirms that metropolitan expansion is overwhelmingly outward, often following transport corridors and converting agricultural land into urban use beyond statutory municipal boundaries.

- New Urban conurbation: The trends indicate that the administrative definition of a city no longer captures the economic reality of the metropolitan region. Decision-making must now account for economic and mobility linkages that extend far beyond statutory city limits.

- For example, Census classifies Kerala's urbanisation at 47.7 per cent (2011), spatial analysis using the DEGURBA framework places it at roughly 80.8 per cent when functionally urban settlements (outside municipal limits) are included.

Governance Deficit: When Cities Lack Economic Agency

A primary structural constraint is the institutional design of Indian cities. The chapter argues that Indian cities are economically central but politically peripheral. The section details this deficit through three main dimensions:

- Institutional Fragmentation: Governance is fractured across ULBs, parastatals, and state depts. Unlike global cities, Indian Mayors lack executive power, creating an accountability vacuum.

- Limited Fiscal Autonomy: Cities generate <0.6% of GDP in own-source revenue (vs. 2-4% in OECD). Heavy reliance on transfers reduces cities to mere implementation agencies for state/central schemes.

- The Compliance Culture: Global cities compete; Indian cities comply. Investing in physical assets (like Metros) without governance reform results in concrete without consequence. Indian cities are currently administered (power dispersed to avoid blame) rather than governed (power concentrated to act).

Land, Housing, Mobility, And Sanitation And Waste Management – The Binding Constraints

This section identifies the specific supply-side bottlenecks that prevent Indian cities from translating their population scale into economic productivity and liveability. It argues that beneath the visible symptoms of congestion and pollution lie deeper structural failures in regulation, planning, and resource management.

Land as Dead Capital

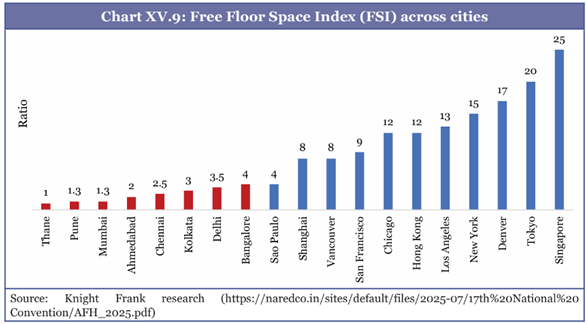

- The FSI Trap: A primary constraint is restrictive Development Control Regulations (DCR), specifically low Floor Space Index (FSI). This artificial scarcity raises land costs and increases the per-unit cost of delivering infrastructure.

- The Sprawl Consequence: Cities expand outward (peripheral growth), leading to concrete without consequence where density increases without the necessary amenities.

- Reforms: While some cities (like Chennai) are moving toward transit-oriented development (TOD) and higher densities, density must be paired with adequate infrastructure (water, transit) to avoid gridlock.

- Additionally, digitisation initiatives like ULPIN (Bhu-Aadhaar) are crucial for securing land titles and making land a tradable, bankable asset.

Mobility

- Congestion causes massive economic losses across major metros. The guiding principle is to prioritise moving people, not vehicles. This requires a high-capacity public transport supported by last-mile connectivity.

- Mass Transit Progress: India has operationalised over 1,000 km of Metro and Regional Rapid Transit Systems (RRTS). The Namo Bharat RRTS (Delhi-Meerut) is a structural shift, functioning as economic infrastructure that reduces travel time and integrates regional labour markets.

- Suggestions to improve mobility

- Scale and digitise buses: Expanding fleets to 40–60 buses per lakh, with end-to-end digital systems, boosts corridor capacity, reliability, ridership, and farebox recovery at low cost.

- Finance-led e-buses: Green Mobility Credit Facilities cut EMIs, lower tariffs, and accelerate e-bus adoption without heavy subsidies.

- Strengthen last-mile mobility: Standardised shared feeders and ONDC-linked apps enable seamless, affordable door-to-door travel.

- Congestion pricing: Citing successes in Singapore and London Survey advocate for Congestion pricing and parking management to disincentivize private vehicle use in dense areas.

Urban Cleanliness and Waste Management

The Survey identifies cleanliness as an institutional and behavioural challenge, not just an infrastructure one. While the Swachh Bharat Mission (SBM) successfully addressed access to toilets, the challenge has shifted to waste processing and behaviour change.

- Door-to-door waste collection has reached 98% of urban wards, but segregation and processing capabilities lag behind.

- The Indore Model (consistently ranking 1st) is attributed to mass behavioural change rather than just machinery. Strategies included leveraging religious leaders, active political leadership, and community engagement to instill civic pride.

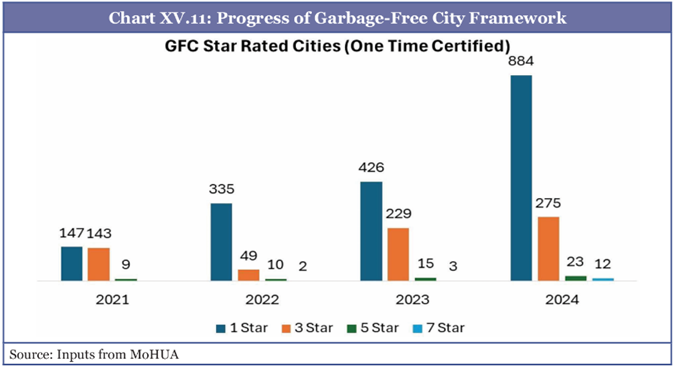

- Future Focus: The focus is now on Garbage-Free Cities ratings, remediation of legacy dumpsites, and managing Cleanliness Target Units (CTUs).

City Upgradation Through Technology Adoption

Technology is being used to upgrade city management. The Smart Cities Mission has established Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCCs) in 100 cities, which use real-time data to monitor services like traffic, water (SCADA), and waste collection, creating a digital baseline for urban governance.

Informality As an Urban Outcome – From Eradication To Integration

Informality in Indian cities; manifesting in slums, labour, and unregistered enterprises; is not a transient failure or an aberration to be eliminated. Instead, it is a structural outcome of rapid urbanisation where formal systems cannot meet the demand for services, housing, and employment.

The Role of Informal Housing and Labour

- Housing: While formal affordable housing, often built on the city periphery, lack connectivity and infrastructure. Consequently, low-income workers choose informal housing to remain close to jobs.

- Labour: The informal workforce is described as structurally indispensable. The text illustrates this with the 2025 sanitation crisis in Gurugram proving that invisible informal labour underpins essential urban services.

- Enterprises: Small, unregistered firms are deeply embedded in urban supply chains, providing goods at competitive prices, though they remain vulnerable to high compliance costs.

Water Security: The Circular Water EconomyWith urban areas generating two-thirds of India's wastewater but treating only 28% of it, the survey pushes for a transition to a circular water economy.

|

Policy Shift: From Eradication to Integration

- Preserving Capital: Displacing informal settlements destroys embedded capital, such as location advantages and social networks.

- Integration Strategy: The recommended approach is in-situ upgrading (providing tenure security and infrastructure) rather than eviction.

- Successful Model: The PM SVANidhi scheme is cited as a model for this integration. The scheme formalised street vendors and gave them access to credit without the need for cumbersome surveys.

Civic Order Without a Social Contract: The Invisible Fault Line In Indian Cities

The quality of urban life is defined not just by infrastructure but by the implicit social contract between citizens and the state. In India, this contract is fragile; while citizens maintain private spaces meticulously, they neglect public spaces because service delivery is unreliable and enforcement is inconsistent.

- Gross Domestic Behaviour: A survey on civic behaviour reveals a contradiction where citizens value public responsibility in theory but abandon it for personal convenience in practice.

- Institutional Equilibrium: Civic order is described as an institutional equilibrium rather than a cultural trait. In global cities, clear rules and credible enforcement make compliance rational. In India, fragmented authority and weak capacity make enforcement uneven, causing the social contract to falter.

The new city: Creative, liveable, and interconnected

The Survey emphasises that liveability depends on organising cities around people's time and choices rather than just infrastructure delivery.

- Ease of Living: Newer Tier-2 cities like Pune and Navi Mumbai currently top the Ease of Living Index as they are not yet overwhelmed by population pressure.

- Agglomeration of Talent: Bengaluru has grown into a global hub despite infrastructure deficits because of its agglomeration of talent and educational institutions.

Planning, Governance and Financing

To address the governance deficit, the government is introducing mechanisms like the Urban Infrastructure Development Fund (UIDF) and the Urban Challenge Fund (UCF) to push cities towards bankable projects and financial discipline.

- From Compliance to Balance Sheets: Advocates shifting from a scheme-compliance mindset to a balance-sheet approach. Cities should prepare statutory 20-year spatial plans and adopt rule-based approvals for FSI to reduce uncertainty.

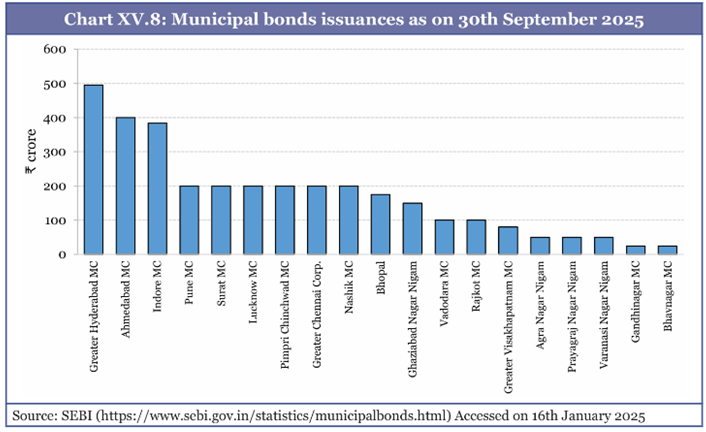

- Fiscal Autonomy: Fiscal effort must be hardwired into institutions through property tax reforms and user charges. Cities that demonstrate revenue effort should be allowed to issue municipal bonds.

- Metropolitan Governance: The text calls for integrated metropolitan authorities to overcome fragmentation, citing the superior management of Noida compared to Gurugram as an example.

Reimagining Physical Infrastructure

Infrastructure must move from isolated asset creation to integrated, climate-resilient systems.

- Integration: Projects are often fragmented; for instance, Metro systems built without Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) principles fail to densify station areas or maximise ridership.

- Climate Resilience: Funding should be conditional on climate plans. Building codes must mandate rainwater harvesting and grey-water reuse, similar to systems in the IIM Kozhikode campus or the solar-powered Cochin International Airport.

- Nature-Based Solutions: Infrastructure should be circular, integrating stormwater drains with wetlands and using tree cover to combat the urban heat island effect.

Developing Social Order and Urban Civic Sense

Civic order should be engineered through rule certainty rather than rule proliferation.

- Credible Enforcement: Fewer, consistently enforced laws with predictable penalties are more effective than dense rulebooks that are weakly applied.

- Design as Nudge: Urban design should act as a behavioural instrument. Legible streets with clear markings, signage, and segregated lanes reduce ambiguity and make the right action intuitive.

- Incentives: Citizens are more willing to comply when they see tangible returns on their taxes through improved services like lighting and drainage.

- Fairness: Enforcement must be fair and provide transitional support for vulnerable groups, such as street vendors, to ensure rules are perceived as legitimate rather than punitive.

The concept of contextual complianceThe section uses the concept of Contextual Compliance to prove that Indian citizens are capable of orderly behaviour when the system supports it. It contrasts the chaos of Indian roads with the discipline observed in the Metro rail systems.

Conclusion: Collective behaviour changes not because people change, but because the system does. |

Non-Tangible Aspects of Future Cities

The Survey argues that beyond addressing the structural deficits (of governance, finance, and infrastructure) future cities require a fundamental shift in design philosophy to become engaging and liveable. It outlines specific principles to transform the look and behaviour of Indian cities:

- Time as the Central Resource: The most liveable cities systematically minimise the time lost to commuting and uncertainty. Future planning must focus on reducing friction by aligning housing, schools, health centres, and workplaces within short travel radii.

- Streets as Social Infrastructure: It advocates shifting from road-widening to street-making, viewing streets as public spaces for interaction rather than just traffic corridors.

- The 8-80 Philosophy: Design should be guided by the principle that streets must be safe and accessible for both an eight-year-old and an eighty-year-old.

- It suggests designating 10-15% of streets in dense areas as pedestrian-first or low-traffic zones to encourage walking, play, and commerce, citing Barcelona's superblock model and Melbourne's laneways as examples.

- Encouraging Creative Density: To become engaging, cities must actively nurture culture by creating low-rent creative zones in inner cities (using underutilised public land) and providing single-window approvals for studios and theatres.

- Integration of Informality Streets should be explicitly designed to accommodate formalised vending spaces, leveraging legislation like the Street Vendors Act 2014.

- Participatory Governance involves inviting citizens into decision-making through neighbourhood councils and open planning processes fostering emotional ownership of the city.

- The Psychological Dimension Cities must inspire imagination. The goal is to transition from survival-oriented urbanism to possibility-oriented urbanism, where public spaces and governance expand what people feel they can achieve.

These intangible aspects are economically vital. In a global competition for talent, cities that exhaust people will lose them, regardless of wages. Conversely, cities that offer dignity and predictability will attract skilled workers and foster an endowment effect, where citizens care for the city as they do for their own homes.

Conclusion

The chapter concludes that while India is spatially and economically urban, it lacks the necessary institutional foundations. It calls for supply-side reforms in land and mobility, integrating informality rather than eradicating it, and empowering municipal governance. An integrated approach combining physical investment with a stronger civic contract is essential for shared prosperity. Ultimately, cities must be empowered to function as economic engines that are inclusive and liveable.

Glossary

| Term | Meaning |

| Agglomeration Economies | The economic logic where density and proximity allow for more efficient matching between workers and jobs, accelerate learning through knowledge spillovers, and enable the sharing of infrastructure and services. |

| Census Towns | Settlements classified as urban based on three criteria: a population greater than 5,000, at least 75 per cent of male employment in non-agricultural sectors, and a minimum population density of 400 persons per sq. km. |

| Statutory Towns | Urban areas officially recognised and governed by specific local bodies like municipal corporations, municipalities, or cantonment boards, regardless of their demographic statistics. |

| DEGURBA (Degree of Urbanisation) | A globally standardised methodology used by the UN and European Commission to classify rural and urban settlements based on population size and density grids derived from satellite data. |

| Night-Time Lights (NTL) | Satellite data measuring light radiance (in nanowatts) used as a marker for urbanisation, population density, and economic activity, often revealing urban sprawl beyond official boundaries. |

| Dead Capital | Assets (primarily land) that cannot function as productive capital due to regulatory, legal, or market inefficiencies, such as unclear titles or restrictive zoning. |

| Floor Space Index (FSI) / Floor Area Ratio (FAR) | A regulation placing a cap on the amount of built-up area allowed per unit of land. Low FSI constraints vertical growth and forces cities to expand horizontally. |

| Own-Source Revenue (OSR) | Revenue raised directly by city governments (e.g., property tax, user charges). In India, this is less than 0.6 per cent of GDP, compared to 2-4 per cent in OECD cities. |

| Regional Rapid Transit System (RRTS) | A high-speed commuter rail system (e.g., Namo Bharat) functioning as economic infrastructure to connect regional clusters, reducing travel time and integrating labour markets. |

| Circular Water Economy | A sustainable management model where treated used water (TUW) is not discarded but reused for non-potable purposes like industrial cooling and construction. |

| Cleanliness Target Units (CTUs) | Difficult and dirty spots, including legacy waste dumpsites, identified for urgent transformation under the Swachh Bharat Mission-Urban 2.0. |

| PM SVANidhi | A government scheme providing credit to street vendors and using a Letter of Recommendation (LOR) as valid identification, facilitating their formalisation and integration into the financial system. |

| In-situ Upgrading | An approach to informality that focuses on improving existing informal settlements with tenure security and infrastructure, rather than evicting residents. |

| Social Contract | The implicit agreement between citizens and the state. The chapter argues this is fragile in India; citizens withdraw from civic responsibility because services and enforcement are unreliable. |

| Gross Domestic Behaviour | A concept (and survey) measuring the civic sense of citizens, highlighting the contradiction where individuals value public responsibility in theory but prioritise personal convenience in practice. |

| Contextual Compliance | The phenomenon where the same individual displays unruly behaviour in one setting (e.g., roads) butdisciplined behaviour in another (e.g., Metro rail) because the latter offers clear design, reliability, and credible enforcement. |

| Urban Infrastructure Development Fund (UIDF) | A fund designed to support Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities in creating viable infrastructure projects, managed by the National Housing Bank. |

| Urban Challenge Fund (UCF) | A performance-linked financing mechanism intended to co-finance bankable urban projects, subject to cities raising a portion of funds through bonds or PPPs. |

| Endowment Effect | A psychological phenomenon where citizens feel a sense of ownership and responsibility for their city, similar to how they care for their private homes, often triggered when governance becomes responsive. |

Mains Question

- "Indian cities are economically central but politically peripheral." Critically examine this statement with reference to municipal governance, fiscal autonomy, and institutional fragmentation.

- Explain how contextual compliance shapes civic behaviour in Indian cities. Illustrate your answer with suitable examples.